PACER Upgrade Leaves Electronic Warehouse of Court Records Incomplete

Research and advocacy groups are exploring ways to restore access to the more than 800,000 cases that were recently removed from PACER, the electronic search and retrieval system for federal court documents.

It is a task made all the more difficult since the records were taken down without public notice or consultation.

With advanced notice, groups seeking to compile and make available federal court documents could have focused on the records that were targeted for removal, said Brian Carver, an assistant professor at the University of California at Berkeley School of Information and director of the Free Law Project. The Free Law Project and Princeton University have teamed up to create RECAP the Law, a browser extension that captures documents downloaded from PACER (at the standard 10 cents-a-page rate) and then makes them available for free on the Web.

“We could have asked RECAP users to focus on the court cases being removed, although it is not clear that we would have made a dent because of the massive number of documents,” Carver said. “Still, we could have made the effort, or perhaps teamed with a commercial provider like Bloomberg to make sure these documents were still available. I also suspect there were technical solutions that, if the right experts were consulted, would have allowed those documents to remain on PACER. If they are in one database, you should be able to migrate them to another.”

Carver is now part of a group spearheaded by Public.Resource.Org that has written to the chief judges of the five affected courts requesting access to digital copies of the records so that they can be made available.

Other efforts are underway as well. Holly M. Riccio, president of the American Association of Law Libraries, said the AALL government relations staff has been in discussions with the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts to advocate for restoration of the documents, to learn about additional changes that may be coming to PACER, and to encourage a more consultative approach to any future changes to the system.

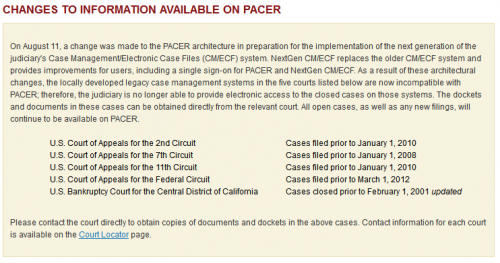

The changes took place on either Aug. 10 or 11. The announcement of the change went up at the same time the documents were removed, an AOUSC spokesperson said. Concerns about the missing cases began to surface last week.

AOUSC spokesman Charles Hall said that the documents were removed because upgrades to PACER are incompatible with the record management systems of a handful of courts. He said that only about 800,000 cases out of more 33 million were affected. He added that all the cases removed are closed, and that the majority come from a single court, the California Central Bankruptcy Court.

“In addition to being closed cases, they happen to be cases that few seemed to need access to,” Hall said. “The removed cases accounted for less than 1/10th of 1 percent of total search requests on PACER.”

But as the BBC pointed out, some of the affected cases are of significant historical interest, including Ricci v DeStefano, a high-profile racial discrimination case heard on appeal by Sonia Sotomayor – now a Supreme Court Justice – when she was on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. All Second Circuit Court of Appeals cases filed prior to 2010 are among those removed by the courts from PACER.

Another spokesperson for AOUSC said she was unaware of how many actual documents or pages are associated with the 800,000 affected cases. She added that the cases were not “deleted,” just taken offline, which gives hope to Berkeley’s Carver that the documents can be put back online, if not by the courts, then by groups like the Free Law Project and Public.Resource.Org.

“The cases were never deleted,” the AOUSC spokeswoman wrote in an email. “No court documents were destroyed. I cannot tell you at this time if they can be, or will be restored.”

AALL’s Riccio said that the fact that the affected cases are all closed does not make researchers feel better about the change.

“In fact, if I am researching how a judge may rule on an issue, it is the cases that have been decided and closed that will be of the greatest interest to me,” Riccio said. “The truth is, you never know when a case may become relevant to your work. And from a research perspective, you want the universe of cases you are pulling from to be as complete and accurate as possible.”

David Mao, the law librarian for the Library of Congress, agreed.

“At the Library of Congress, one of our missions is to ensure that the information we collect, including government information, is preserved and available to the public,” Mao said. “It is important that information be as complete and comprehensive as possible. To the extent that once available information is now unavailable, that makes our job more difficult.”

Carver said that the situation is made worse by the fact that there is no list of cases affected, and that when you search for a case that has been removed, no results are returned.

“When I read the BBC article about the Ricci v DeStefano case being removed, I realized that I had the case number for that particular case,” Carver said. “So I decided to see what would happen if I searched for it. PACER charged me 10 cents for the search, and I got the standard notice that no records could be found. There was nothing about the case being removed, or how else I might access it. PACER treats it as if the case never existed.”

The documents are still accessible from the individual courts, but it’s a laborious and expensive process to get them, as outlined in this post from Professor Leslie A. Street at the University of North Carolina School of Law. Along with being an extremely helpful guide to how to obtain these documents, Street’s post reveals that the clerks in at least one of the affected courts were unaware that their documents had been removed from PACER.

Hall, the AOUSC spokesman, said his office is still trying to get a handle on other changes that will be coming to PACER as a result of the upgrade. One enhancement he thinks users will like is that they will no longer have to login separately to each district court to search for that court’s documents. Rather, they will stay logged in as they navigate from court to court.

Riccio said, as a practical matter, that particular enhancement may not be that useful. She said she normally searches all courts instead of specific courts, and that most browsers remember login information, so signing in again is fast and easy. One enhancement she’d like to see in PACER is the ability to search by judge, in addition to fields like defendant’s name and case number that already exist.

“We’re just hopeful that moving forward, there will be more notice and more collaboration, and that the courts will seek input from a variety of users when making decisions that affect those users,” Riccio said.

The FOIA Project itself is a heavy user of PACER. Computer experts at the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, one of the FOIA Project partners, has developed algorithms that identify FOIA cases in PACER and allows the Project to pull the cases into our Case Search mechanism, which contains the dockets and other documents for more than 5,000 FOIA cases.

Many services use PACER in this way, developing programs to identify cases of interest, adding value to those records in some way, and making them available for free (as the FOIA Project does) or as part of a subscription service. Another unknown about the changes to the PACER architecture is whether those changes will force organizations’ to alter the underlying mechanisms they use to collect information from PACER.

Here are some links to what others are saying about the changes:

* From the Washington Post;

* The above-mentioned BBC story;

* From Carver’s Free Law Project blog;

* The North Carolina School of Law post already noted above;

* From Ars Technica;

* From The National Law Journal (free reregistration required);

* From the Wall Street Journal Law Blog;

* A piece with lots of gripes about PACER from the zine TechDirt;

* From the federal technology blog Fed Scoop;

* Here’s an editorial on the changes from The News Herold of Panama City, Fla.

Want to add your thoughts to this discussion? Please comment below, share your thoughts on our Facebook page, Tweet at us @foiaproject, or email gjmunno@syr.edu.

Unfortunately, the Free Law Project has decided to charge other organizations money to access RECAP documents, and it now denies access to organizations which refuse to pay. The new version of the RECAP plug-in only uploads documents to the FLP’s own CourtListener site, while other sites, such as PlainSite and the United States Courts Archive, are no longer being updated. This decision was made in secret with no public discussion, and it was made despite the FLP’s stated position that court documents should be free and freely available to everyone. For more information, please see https://www.plainsite.org/articles/20171130/why-plainsite-no-longer-supports-the-recap-initiative/