Scrutinizing Attorney Fee Awards in FOIA Litigation

Note: The FOIA Project wishes to thank Christine Mehta who prepared an initial draft of this report during her time as a Newhouse faculty member at Syracuse University.

A congressional report published in January 2016 found that “FOIA is broken,” and highlighted a culture within the federal government of “unlawful presumption in favor of secrecy when responding to Freedom of Information Act Requests. [1]” The report pointed to government abuse of FOIA exemptions to unlawfully withhold information, excessive fees, and delays in response time from agencies as the key factors in eroding public trust and use of the law. In the face of blatant dismissals of requests for information on the part of federal agencies, often the only channel for remedy is a lawsuit. “Requesters shouldn’t need a lawsuit to get responsive documents,” wrote the authors of the congressional report.

No, they shouldn’t. But they do.

The result is costly. In 2016, the Obama Administration reported it spent $36.2 million defending FOIA-related lawsuits. These costs rose to $40.7 million in FY 2017 – nearly double the level of $22.2 million during FY 2010 [2]. The government’s costs, however, fail to capture the cost to those bringing suits against federal agencies to enforce their right to information under FOIA. The year 2016 marked the 50-year anniversary of FOIA. To commemorate the landmark legislation, ProPublica published the article, “Delayed, Denied, Dismissed: Failures on the FOIA Front.”

Journalist Cezary Podkul wrote in the article, “Short of suing the agency – an expensive proposition that could take years if the agency actively resists and appeals when it loses – I can’t find out. [3]” Podkul’s statement is illustrative of the continued frustration with FOIA, and the reluctance to use the courts to force FOIA compliance.

The FOIA Project set out to assess information reported by the Department of Justice (DOJ) on FOIA litigation and compliance, and in particular, the importance of recovering fees and costs of litigation from federal agencies for lawyers and plaintiffs who take them to court. The FOIA statute provides that courts “may assess against the United States reasonable attorney fees and other litigation costs reasonably incurred …[where] the complainant has substantially prevailed,” and requires the Attorney General to submit an annual report to Congress identifying the cases where such awards were made and their amounts.

FOIA attorneys have previously told the FOIA Project that the Justice Department’s reporting on costs was inaccurate [4]. The FOIA Project set out to examine whether there was more systematic underreporting in DOJ’s annual listings of attorney fee awards.

During the summer of 2018, using the DOJ list covering 2016 [5], the FOIA Project reached out to 97 attorneys who were not listed by the DOJ as receiving awards [6]. After further follow-up, the project successfully reached 42 attorneys. Four out of ten (17) reported that they received fee awards, while the remaining six out of ten (25) said they had not received any fees.

Since we were not able to contact every attorney handling cases on the 2016 DOJ list, these results may not have uncovered all cases where attorney awards were made but not listed [7]. But even these 17 cases represents a 22 percent increase or error rate over the number of cases that the DOJ had reported having fee awards. We are indebted to our legal intern, Taylor Lamb, a law student at Georgetown University, for conducting this survey and for gathering the additional data needed for the award amounts presented in Figure 1 later in this report.

While we did not examine whether the amount of the fee awards reported by DOJ were at least accurate, an earlier 2016 report by the General Accountability Office (GAO) entitled Freedom of Information Act: Litigation Costs for Justice and Agencies Could Not Be Fully Determined reported finding significant misreporting in award amounts [8]. GAO’s investigation focused exclusively on cases where DOJ reported attorney fees had been awarded. In addition to collecting information on the staff time spent by the government in defending these cases, the study compared the amounts reported by DOJ for 112 such awards with those recorded as being paid by the agencies who were the actual defendants in these cases.

While agencies for only half of these 112 cases kept such records according to the GAO, its study still turned up at least 10 cases where amounts differed – sometimes by substantial amounts. GAO’s report further found that the Justice Department fails to require agencies paying these awards, or DOJ’s own attorneys handling FOIA cases, to track fee awards. In addition, the GAO reported that “officials in Justice’s Office of Information Policy [asserted] the inclusion of costs resulting from settlement agreements and appeals is not required to be included in the department’s reports to Congress.”

The evidence seems clear that Justice’s Office of Information Policy significantly underreports both the number of cases with attorney fee awards as well as amounts of such awards. Despite the congressional mandate requiring reporting of the amount of attorney fee and cost awards in each FOIA lawsuit, the Department of Justice has failed to take its responsibilities seriously and institute the necessary recording procedures needed to accurately track these awards.

Going After Fee Awards

There are currently more than 200 federal statutes in the United States that allow for fee-shifting – FOIA among them [9]. According to the American Bar Association, fee-shifting provisions “are designed to attract lawyers to public interest cases that would otherwise not seem worth the investment. [10]” Indeed, the Supreme Court has ruled that fee-shifting provisions are designed to encourage worthy plaintiffs to hire an attorney to press their claim. In Kay v. Ehrler, 499 U.S. 432 (1991), the Court ruled that an attorney representing himself in a civil rights action was not eligible for attorney fees.

The traditional rule for apportioning costs in the United States is that both parties to litigation should bear their own costs. Fee-shifting provisions are an exception in which the government waives its sovereign immunity from suit by specifically allowing a prevailing plaintiff to recover fees, including attorney fees.

Further, even if a plaintiff is eligible for a fee award, the court has discretion to decide whether the plaintiff is entitled to an award. To show entitlement, courts use a four-factor test contained in the Senate Report on the 1974 FOIA amendments. Those four factors assess whether disclosure would benefit the public interest, whether the requester has a commercial or personal interest in obtaining the records, and whether the agency had a reasonable legal basis to withhold the records.

Even though FOIA provides for fee awards to plaintiffs that substantially prevail, fee awards are by no means routine because of the degree of discretion granted to the district court judge. Because the Supreme Court’s ruling in Buckhannon Board & Care Home Inc. v. W. Virginia Dept of Health & Human Resources, 532 U.S. 598 (2001), in which the Court found that awards under federal fee-shifting provisions were only available when the plaintiff was awarded relief on the merits, was found to apply to FOIA, fee awards were subsequently limited to instances in which a district court had ordered an agency to change its legal position as a result of the suit. Congress specifically amended the attorney fees provision in FOIA in the OPEN Government Act of 2007 to make clear that Buckhannon did not apply to FOIA. Instead, the definition of substantially prevailing was changed to apply in circumstances where the plaintiff obtained relief by court order or a voluntary or unilateral change in the agency position, providing that the claim was not insubstantial.

Finally, because plaintiffs are required to set out all their initial claims when they file their complaint with the district court, nearly everyone who believes they are eligible for a fee award includes such a claim in their complaint. As a practical matter, most requesters who file suit do so as a result of the agency’s failure to respond within the 20-day statutory time limit. This means that claims for attorney fees must be made before there is any basis for accessing the agency’s final response to a request.

Why Fee Awards Matter

Going to court is costly. No matter how simple the case. Amongst lawyers, FOIA cases have a reputation of being “open and shut” cases, requiring little of an attorney’s time and resources. However, even the shortest and simplest of cases can accrue fees that are prohibitive for the average person, and some FOIA cases can be long and drawn-out [11]. A lawyer at Public Citizen, a nonprofit that represents public-interest FOIA lawsuits, disputed the notion that FOIA litigation is not “that expensive.”

“It’s all relative,” she said. “Doing the complaint, status hearings and reports, discussions with the other side…a lawyer will have charged thousands of dollars. Journalists who aren’t backed by a large organization, small nonprofits, or average people, they don’t have the funds to litigate.”

To gain a better picture of the process of seeking and negotiating fee awards in FOIA cases, the FOIA Project conducted phone interviews with 22 attorneys in October 2018. All the attorneys interviewed by the FOIA Project stated that the fees and costs recovered from federal agencies in FOIA lawsuits were generally a fraction of the actual cost. Several stated that recovering attorneys’ fees was a matter of principle, rather than practicality, as the amounts awarded were insufficient to cover the real costs of litigation.

This was confirmed by the actual size of awards. Most attorney awards were under $10,000. But there were exceptions. The payment of attorney fees and costs amounted to $100,000 or more in at least five cases in 2016. See Figure 1.

One lawyer who regularly represents FOIA cases for a large nonprofit put it bluntly, “You can’t fund your operations on attorneys’ fees. They are a drop in the bucket. It’s nice to get, to hold the government accountable. But you’re never going to get all of your attorneys’ fees even if you win.” The same lawyer went on to clarify that the same principle applies in all fee-shifting statutes, not just FOIA. “Fee-shifting is there to deter bad conduct, to ensure some access to the courts, and not be completely out of pocket with lawyers’ fees,” he said [12].

Figure 1. Amounts Awarded in 2016

The majority of attorneys interviewed reached settlements with federal agencies, and agreed to fee awards as part of larger settlement negotiations. For some lawyers, fee awards were on the table as negotiating chips. One attorney who worked for a private law firm said, “Sometimes you’ll forgo attorneys’ fees as part of leverage for your client. They can work a leverage for negotiation in settlement in all kinds of cases. [13]” For other lawyers, fee recovery was a separate question from the rest of the case. The lawyers involved in settlement negotiations said after the case was settled, they would send a letter to the agency requesting a fee award based on a spreadsheet of costs, including filing fees, time spent by attorneys on the case, and so on. All said that the federal agency concerned would negotiate for lower rates, as is the case in other types of cases where fee-shifting statutes apply.

Cecilia Segal, a lawyer with the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC), said she had noticed the government responding more negatively to fee award requests in the past two years. “I’ve noticed the government back more strongly with ‘I can’t believe you’re seeking fees at all’. But you know, we’re entitled to fees…the government knows it can’t get away with paying no fees,” she said.

A few attorneys interviewed escalated beyond settlement negotiations and filed petitions in court seeking fee awards. A solo practitioner in California, Chris Sproul, who specializes in environmental litigation was one of the few lawyers interviewed who cited FOIA litigation as integral to his practice. He pointed to FOIA’s fee-shifting statute as critical to his ability to represent cases brought by small nonprofits and activists. Sproul almost always files fee petitions in order to maximize the amount awarded by the court. “FOIA settlement [for fee awards] has been lower than average [compared to other types of cases]. I’ve never been able to settle for a large fee recovery in FOIA cases, ever.”

Several lawyers pointed to the challenge in balancing the need to reflect the real cost of litigation in fee awards, and “overplaying your hand” in Segal’s words.

Rise in FOIA Lawsuits

Despite the passage of the 2016 FOIA Improvement Act which wrote the “presumption of disclosure” explicitly into the law [14], denials of administrative requests under FOIA persist and FOIA litigation is increasing. All lawyers agreed that fee-shifting provisions are critical to public interest litigation. “Fee-shifting is better than no fee-shifting,” said Patrick Llewellyn, another lawyer at Public Citizen.

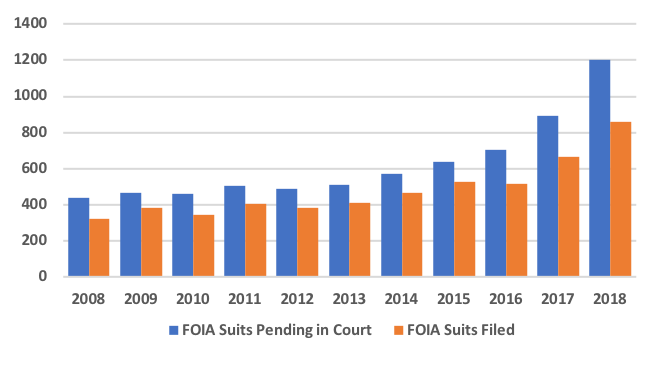

The adequacy of attorney fee awards becomes even more urgent as the public turns more often to litigation in FOIA cases. “Compared to an average of 402 FOIA suits per year during the Obama Administration, the rate of filing since President Trump assumed office has more than doubled. While suits rose during the latter years of the Obama Administration, the 860 suits filed in FY 2018, represent a 67 percent increase over filings during the last full fiscal year of the Obama Administration. [15]”

Figure 2. FOIA Litigation Reaches Record Highs in FY 2018

Public interest FOIA litigation filed by media organizations, reporters and nonprofit organizations has been driving much of this increase. By the end of the Obama Administration, for example, nonprofits’ annual rate of filing was about 200 cases per year. As of the 2018 fiscal year-end, nonprofits’ annual filing rate reached 500 lawsuits, approximately 56 percent of all FOIA lawsuits filed [16]. Among these, a number of smaller nonprofits, including those formed during the first year of the Trump Administration are showing up as frequent litigants. Media lawsuits, particularly those filed by individual reporters, have also jumped [17].

As long as the federal government continues to fail in its obligations under FOIA to release information at the administrative stage, it will be crucial to continue monitoring the ability of the public to find legal representation willing to challenge such unlawful behavior in court.

Footnotes

[1] FOIA is Broken: https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FINAL-FOIA-Report-January-2016.pdf.

[2] Summary of Annual FOIA Reports for Fiscal Year 2017, Office of Information Policy, Department of Justice, available at https://www.justice.gov/oip/page/file/1069396/download.

[3] ProPublica. “Delayed, Denied, Dismissed: Failures on the FOIA Front.” July 21, 2016. https://www.propublica.org/article/delayed-denied-dismissed-failures-on-the-foia-front.

[4] See, for example, http://foiaproject.org/2013/04/23/did-the-doj-accurately-report-on-your-foia-lawsuit/ and http://foiaproject.org/2013/04/25/another-error-in-doj-compliance-and-litigation-report/.

[5] Department of Justice. “2016 Litigation and Compliance Report.” March 7, 2017. https://www.justice.gov/oip/2016-foia-litigation-and-compliance-report-0.

[6] Due to time and resource limitations no attempt was made to contact attorneys in every FOIA case. Attorneys contacted and those who responded also could not be considered a statistically representative sample so the error rate found cannot be extrapolated to the complete set of cases.

[7] In addition, at least 5 of the lawsuits on DOJ’s 2016 list were still ongoing so fee awards had not yet been determined.

[8] Government Accountability Office, Report to the Committee on the Judiciary, U.S. Senate. “Freedom of Information Act: Litigation Costs for Justice and Agencies Could Not Be Fully Determined.” September 2016. Page 10. Available here: https://www.gao.gov/assets/680/679631.pdf.

[9] McKinney Law. Indiana International and Comparative Law Review. Vol. 15.3. “Attorney Fee-Shifting in America: Comparing, Contrasting, and Combining the American Rule and English Rule.” David Root. 2005. Available here: https://mckinneylaw.iu.edu/iiclr/pdf/vol15p583.pdf. Page 588.

[10] American Bar Association. “Fee-Shifting.” June 11, 2015. Available here: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/delivery_legal_services/reinventing_the_practice_of_law/topics/fee_shifting/.

[11] Center for Public Integrity. “After years-long FOIA battle, the Energy Department pays the Center for Public Integrity $5K in legal fees.” June 4, 2018. Available here: https://www.publicintegrity.org/2018/06/04/21829/after-years-long-foia-battle-energy-department-pays-center-public-integrity-5k.

[12] Interviewed over the phone on October 16, 2018 by TRAC staff, the attorney expressly asked for anonymity.

[13] Interviewed over the phone on October 17, 2018 by TRAC staff, the attorney expressly asked for anonymity.

[14] PBS. “Obama administration sets new record for withholding FOIA requests.” March 18, 2015. Available here: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/obama-administration-sets-new-record-withholding-foia-requests; Department of Justice. “President Obama Signs the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016.” June 30, 2016. https://www.justice.gov/oip/blog/president-obama-signs-foia-improvement-act-2016.

[15] See November 12, 2018 FOIA Project annual report entitled: FOIA Lawsuits Reach Record Highs in FY 2018, available at: http://foiaproject.org/2018/11/12/annual-report-foia-lawsuits-reach-record-highs-in-fy-2018/.

[16] “FOIA Suits Filed by Nonprofit/Advocacy Groups Have Doubled Under Trump,” published October 18, 2018 by the FOIA Project, http://foiaproject.org/2018/10/18/nonprofit-advocacy-groups-foia-suits-double-under-trump/.

[17] “Media Lawsuits Seeking Government Records Jump Under Trump,” published August 2, 2018 by the FOIA Project at: http://foiaproject.org/2018/08/02/media-foia-lawsuits-jump-under-trump/.