FOIA Suits Rise Because Agencies Don’t Respond Even As Requesters Wait Longer To File Suit

In the last few years, the number of FOIA lawsuits has risen dramatically, much faster than the rise in FOIA requests.1 Anecdotal reports suggest that delays in receiving responses to FOIA requests may be increasing and a reason for rising litigation.2 Long delays have always been a hallmark of FOIA. Should these trends continue and cause requesters to head to court, FOIA litigation will also continue to increase. During the summer of 2019, TRAC’s summer legal intern, Samuel Hanks, a second-year student at Georgetown University Law School, explored the possible impact that delays in receiving responses could be having by assembling relevant data and then interviewing plaintiffs’ attorneys to learn more about how delays affect their litigation strategy.

Samuel compiled response dates from the 222 FOIA cases filed in federal district courts from January 2019 through May 2019, noting whether the agency responded to the request, and how much time passed before the lawsuit was filed. These results were then compared to an analogous set of FOIA cases filed from January through May of 2015, a period during which there were 125 such cases filed. 3

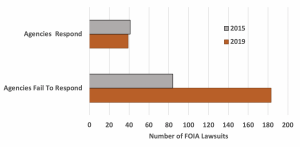

The study found that the number of suits challenging agencies substantive responses had not materially changed. Their numbers remained relatively small. Instead, most litigation occurred when agencies failed to respond to FOIA requesters. As shown in Figure 1, suits filed when agencies failed to respond to FOIA requesters have skyrocketed. See Figure 1.

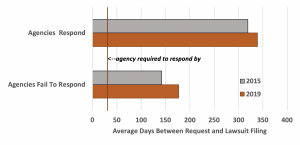

Commentators have speculated that requesters now are heading to court more quickly when agencies fail to meet the time limits set for responding to their requests. This was not born out by the data. The statute provides that agencies need to respond within 20 business days.4 However, in 2019 requesters waited an average of nearly six months (177 days) before filing suit when they failed to receive any response to their request. In addition to not jumping into court quickly when an agency didn’t respond, requesters actually waited an average of over 30 days longer before filing suit in 2019 than they had in 2015.

Where agencies did provide a substantive response, average days between a request and the filing of a suit was even longer – over 11 months (339 days). As shown in Figure 2, this period also increased between 2015 and 2019.

Further Details on What the Data Show

Changes in the make-up of FOIA litigation

- In both 2015 and 2019, the majority of FOIA litigation resulted when agencies failed to respond to FOIA requesters. In 2015, two out of every three suits (67%) occurred after the agency failed to respond. In 2019, in more than four out of every five suits (82%) the agency had not responded.

- Agencies Provide Substantive Response. There was no material change in the number of suits filed after the requester received the agency’s substantive decision. In 2015, 41 suits occurred after an agency provided a substantive response. While in 2019, 39 suits occurred challenging the agency’s substantive response.

- Agencies Fail To Respond. The rise in litigation over this four year period was entirely driven by suits filed because the agency had failed to respond to the requester. In 2015, 84 suits were filed after the agency failed to respond. By 2019, this number had risen to 183 suits.

Days between request and lawsuit filing

- Agencies Fail To Respond. When litigation resulted after agencies failed to respond, generally requesters did not immediately jump into court. Average wait times actually lengthened somewhat between the filing of a request and suit being filed in 2019 as compared with 2015. The average wait times between the request and filing of the suit were 142 days in 2015 and 177 days in 2019.

- Agencies Provide Substantive Response. While agencies did provide a substantive response, agencies were not responding within statutory limits and typical response times had not improved. Indeed, requesters’ average wait times from request to suit filing had lengthened from an average of 319 days in 2015 to an average of 339 days in 2019. However, despite these much longer delays compared to when an agency failed to respond at all, requesters showed a willingness to wait in part perhaps because the agency did a better job of keeping in contact and/or indicating that progress was being made in processing their requests.

Between 2015 and 2019, there was also an increase in the amount of time that requesters waited after their last contact with the agency before suing. This was true both when agencies failed to respond, as well as wait times after the agency did provide their response.

In summary, this study lends no support to a commonly expressed concern that FOIA litigation has increased because requesters are not giving agencies time to respond, but are jumping into court more quickly. Indeed, if anything, the opposite is true.5

Because taking the agency to court still only occurs infrequently in FOIA matters, much more goes into the decision to file suit even when lengthy response delays are encountered. The study next examined some of the factors entering into this decision of whether or not to file.

FOIA Attorneys Provide Perspective on When and Why to File Suit

From the group of attorneys representing plaintiffs in the 2019 dataset, Samuel queried over 90 attorneys, representing more than half of the named plaintiffs, receiving responses from 27 of them, including phone interviews. The attorneys represent large media organizations, public interest groups, and a variety of law firms. Because of the nature of ongoing litigation, many of the attorneys could not speak on the record and their names and employers will remain anonymous.

Despite their many different perspectives, most of the attorneys interviewed readily admitted that requesters should be willing to sue the agency more quickly, especially if certain red flags appear. The most commonly cited indicator of agency unresponsiveness was, not surprisingly, a complete lack of communication. Other attorneys cited spurious denials of fee waivers, agencies repeatedly claiming the request was overbroad, claiming to receive the request weeks after it was submitted, and overuse of Glomar denials or similar exemptions that did not fit the request. These agency responses (or the lack thereof) were frequently cited as indicators that a request may need to be resolved through the courts.

Many of the interviewed attorneys acknowledged that requesters often wait too long and allow the agency to set the framework of the interaction. This was especially true among attorneys who had recently begun FOIA litigation. Attorneys who had less than two years of FOIA experience frequently noted that after their initial experience with FOIA, they would sue more quickly in the future.

For example, two attorneys noted that they had wasted time by appealing requests that had not been answered, believing at the time they needed to do this to prove they had exhausted their administrative options. Another noted that if the request was likely to be rejected, they would sue as soon as the statutory deadline passed, preventing the requirement to appeal from kicking in later in the process.

Attorneys who worked for media or advocacy organizations were more likely to be cautious about beginning lawsuits, viewing them as a drain on limited resources. These attorneys agreed that FOIA officers are well-meaning public servants that rarely have any control over the policies that cause problems. Therefore, they worked on developing good relationships with FOIA staff, trying to be persistent (or even “pestering”) for as long as the agency maintains communication. These attorneys agreed that phone calls, in particular, were much more effective than any other form of communication. Additionally, many of the attorneys said that a willingness to identify the most important documents in the request often hastened the process. However, attorneys still pointed out that once the agency stops communicating there is little reason to wait. No attorney suggested waiting more than three months without word from the agency on a request of standard size and complexity before filing a complaint.

The attorneys referenced a variety of other factors in deciding when to sue, including the needs of the client (especially important for media organizations or firms who represent journalists with deadlines), the expected timeline of the case compared to any timeline given by the agency, the size of the request, previous history with the agency, and resource management. Those at public interest or media organizations also considered whether a lawsuit could impact the judicial interpretation of the law.

Regardless of the eventual success of litigation, there was a relatively even split over the question of whether courts prefer requesters to wait some amount of time after the statutory deadline (in order to demonstrate some good faith, or in recognition of the existing backlogs). One attorney at a firm specializing in FOIA work stated that courts simply do not care about this, and resource management was the only reason to wait to file a lawsuit. Conversely, an attorney at an environmental advocacy group said that the organization almost never sued immediately on the deadline, as waiting longer was viewed as being more reasonable. An attorney at a national law firm agreed, commenting that judges do not like to see cases filed on day 21.

Attorneys had a few different comments about why lawsuits seem more effective. Notably, interviewees had nearly unanimous positive comments about working with the Department of Justice. Justice Department attorneys have no vested interest in the documents and are thus more likely to try to find compromises and solutions. Attorneys who file complaints regularly often had good working relationships with the Assistant United States Attorneys in their district, and this contributed to the feeling that lawsuits produced results. Additionally, an attorney at a national civil rights organization pointed out that once the complaint is filed, the lawsuit can be used to set explicit deadlines that would not otherwise be met. An attorney at a large international firm was blunter, saying that a lawsuit that produced even a tiny number of documents was better than nothing. Attorneys with more FOIA experience were more likely to point out that an important negotiation in the lawsuit was the production schedule, as the agencies are likely to have very low page-per-month numbers.

Concerning agency practices

Whether agency practices have decreased response times or not, attorneys identified several practices that had exacerbated the issue.

Political review

Multiple attorneys, two with decades of FOIA experience at different types of organizations, said that the process of political review at the Department of the Interior6 and EPA7 delay requests and increase the likelihood of a lawsuit.

The new EPA rule

The attorneys had a wide variety of reactions to the recent FOIA rule promulgated by the EPA.8 Some attorneys felt the rule severely decreased transparency, while others predicted it would have little practical effect. At least two attorneys suggested that the rule change codified what were already informal policies and may serve to normalize controversial practices.

Closing requests

Although this may be part of a broader effort to quickly reduce backlogs, three attorneys noted that agencies were closing requests early after putting the burden of reply on the requester. An environmental advocacy lawyer had seen agencies demand that the requester narrow the request and then close the request if there was no response in a short period of time. Other attorneys had seen agencies respond to older requests and close them if there was no communication indicating that the requester still wished to receive the documents.

Misuse of exemptions

A few attorneys mentioned different exemptions—including Glomar responses, exemption 4 through the rise of federal contractors, overly broad requests—that are being applied in new or misleading ways to requests that clearly do not fall under the exemption.

Conclusion

Despite the practices listed here—or perhaps with the exclusion of the EPA rule—the attorneys interviewed generally refrained from saying that FOIA procedures had become substantially worse in recent years. Instead, they pointed out that the agencies with reputations for being difficult to work with were still difficult to work with, and that the huge spike in FOIA litigation as well as lengthening wait times had made the process more cumbersome for everyone involved.

The huge jump in FOIA lawsuits is not explained by the modest increase in the number of FOIA requests that agencies report receiving.9 Because of current events, less transparency in other branches of government, or simply more people being aware of FOIA and also being willing to sue when agencies fail to respond, many more people are taking federal agencies to court when they fail to respond to their requests. Litigation is, of course, much more resource-intensive for everyone. Yet agencies are doing very little to combat this trend. Without changes to reduce delays in responding to requesters, costly FOIA litigation appears likely to continue unabated.

——–

1. The number of FOIA requests has increased by 21 percent over the most recent five year period where data are available (FY 2014-FY2018), while FOIA lawsuits have jumped by 64 percent over this same period. See Summary of Annual FOIA Reports for Fiscal Year 2018 covering FOIA requests and Annual Report: FOIA Lawsuits Reach Record High in FY 2018. For FY 2019 FOIA lawsuit numbers see September 2019 FOIA Litigation with Five-Year Monthly Trends.

2. See The Freedom of Information Act is getting worse under the Trump administration, Agency FOIA backlogs creep up despite governmentwide reduction, and U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.

3. These cases represented all FOIA cases filed involving a single FOIA request to a single agency during these time periods. This made it possible to isolate and measure elapsed times between requests, acknowledgment letters, agency substantive response (if any), administrative appeals (if any) and filing times. This population did not include lawsuits involving multiple defendants and/or multiple requests. These single request/single agency suits made up over half of FOIA lawsuits. They were the same proportion of litigation in the two years (58.7% in 2015, and 57.7% in 2019). No difference was found between the single request/single agency lawsuits and the FOIA lawsuits not included in this study in the proportion of litigation resulting after an agency’s failure to respond. However, because the study did not attempt to assess response times when multiple agencies and/or requests were involved, response time results based upon the study population may not wholly generalize to FOIA lawsuits excluded from the study.

4. This can be extended an additional 10 business days in exceptional circumstances and should be faster yet if expedited processing is needed.

5. The data set was not large enough to compare patterns for specific agencies given the multitude of separate agencies responsible for responding to FOIA requesters. For example, while there were many Department of Justice cases in the data set, those requests are broken up among 36 different “components”, each with its own FOIA office. See DOJ Reference: Listing and Descriptions of Department of Justice Components, FOIA Requester Service Centers and FOIA Public Liaisons, Descriptions of Information Routinely Made Publicly Available, and Multi-track Processing Information. Many agencies have different policies and practices. Thus, these generalizations while true for federal FOIA litigation as a whole, do not necessarily reflect litigation patterns with respect to any specific agency.

6. See Interior’s internal FOIA policy gives political appointees sign-off on document releases, raising concerns by Ellie Kaufman, CNN.

7. See EPA rule lets political officials block FOIA document requests by Meg Cunningham, Roll Call.

8. For an explanation of the rule, see New EPA rule could expand number of Trump officials weighing in on FOIA requests by Miranda Green.

9. See Footnote 1 above.